|

||||

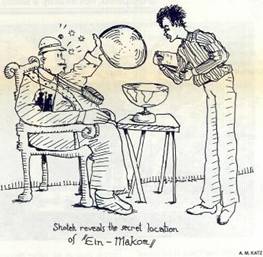

The Jews of Ein-Makom

Volume 3 , Issue 4 (March, 1990 | Adar, 5750) Recently, I had the opportunity to speak with

Raphael Shoteh, the well‑known

Moroccan/Israeli traveler. Shoteh is best known

perhaps for his discovery of the last Jews of China, tracing them in the early 1980's

to a small, aging community on Mauritius, an island between South Africa and

Australia. What follows is an excerpt from an interview with Shoteh, conducted by mail and in person at his home in Berkowitz: How did you come upon Ein‑Makom? I've looked for it in several atlases and can't seem to find it. Shoteh: That's because Ein‑Makom is the name the Jews give it. Naturally, the town has an ordinary English name which it uses for official business. Berkowitz: And the official English name?

Shoteh: I cannot divulge it. The Jews of Ein‑Makom requested that I maintain their privacy. They fear tourists and journalists who may destroy their way of life. Berkowitz: So, we're

talking about an isolated, traditional community like Squaretown

in upstate Shoteh: Not really.

Although the Jews in Ein‑Makom are committed to

Judaism, they are not interested in re‑creating shtetl

life. Many of them have jobs within the community ? as carpenters, teachers and

the like ? but others work in the nearby city. Like Jews elsewhere in Berkowitz: If that is so, how do they keep their town a secret? If someone works in an office, it's only natural for the people around her to ask questions. What does a person from Ein‑Makom say when someone asks, ?Where do you live?? Shoteh: She would simply give the name of the nearby town. No one thinks to question it. Remember, the Jews there do not dress differently from anyone else. And they speak without accents. No one knows they come from an unusual community. Berkowitz: So far, I don't have a clear image of Ein‑Makom's Jews. Let's start with religious life. How many shuls are there in Ein‑Makom, and what are the denominations? Shoteh: First of all, do not think in terms of the standard denominations. There are two synagogues in Ein‑Makom, but they don't call themselves Orthodox or Conservative or Reform. One is traditional, the other liberal. Berkowitz: Are they on speaking terms? Shoteh: Yes. Let me explain how the synagogues are structured: the two congregations share a split‑level building. The traditional congregation is on one level; the liberal congregation is on the other level. Berkowitz: I am familiar

with that kind of arrangement. I've seen it in places like Park Slope in Shoteh: Perhaps. But these two congregations share meals, baby‑sitting services, even Sifrei Torah if necessary. The relationship is quite friendly. Berkowitz: Was this always the case? Shoteh: Well, a few years ago, four men attempted to split the two synagogues. Interestingly, two were from the liberal side and two were from the traditional side. They started a campaign and tried to incite animosity between the two groups. Berkowitz: Were they successful? Shoteh: Not very. They were asked to leave the community. You said you were from Park Slope? Berkowitz: Yes. Shoteh: I'll have to

check my notes, but I seem to remember that these four men were rumored to have

moved to that part of Berkowitz: Getting back to the two congregations. How do they differ? Shoteh: Well, as I've said, one is traditional and the other is more liberal. But basically, it boils down to a single issue: the role of women. In the liberal congregation, women take a more active role in the services. Berkowitz: I suppose the women wear kippot and taleisim? Shoteh: Again, I ask that you put away your preconceptions. In fact, the women in the liberal congregation do not wear kippot or talitot. They consider it a violation of the prohibition against cross‑dressing. Also, even in the liberal congregation, women sit separately from the men. They discovered that the men were too distracting. Berkowitz: So, in what way do the women of the liberal shul have a more active role? Shoteh: They are called to the Torah and lead the services. Recently, the congregation has hired a woman rabbi. Berkowitz: Isn't this a halakhic problem for them? Shoteh: It is a liberal congregation, after all. They themselves admit their practices are not all halakhic. Berkowitz: What about the traditional shul? Shoteh: The traditional shul is just that. Women are not chazanot [cantors], nor do they read from the Torah. All of the women wear skirts or dresses that reach below the knees, and all the married women cover their hair, in the synagogue and outside. Berkowitz: So the town employs a wig‑maker? Shoteh: No. The traditional women of Ein‑Makom feel wigs are uncomfortable and hardly in the spirit of the law. Not when the average wig is more attractive than the average natural head of hair. Berkowitz: How else do the two groups differ? Shoteh: Of course there are some differences in interpretation of the law. Men in the traditional camp grow beards and wear their tzitzit out. Some of them wear dark suits and black hats, but those things are considered symbols of commitment, not achievements in themselves. For example, a man who dressed that way but spoke lashon harah would be scorned by his peers. Men in the liberal camp dress more casually. Remarkably, however, both groups are punctilious in the major facets of Jewish life. Take kashrut, for example. As far as I could tell, both traditional and liberal Jews ate only kosher food. No one ? on either side ? will eat in a non‑kosher restaurant, even to have a salad. Berkowitz: That sounds a bit severe. Shoteh: Not really. Especially when you consider that they all eat in each other's houses. Most of them are vegetarians, which makes life a lot easier for those who are careful about separate china and silverware. In fact, chalav yisrael [milk processed under Jewish supervision] is found in all of their houses. They maintain that it tastes better and helps them understand difficult sections of Torah. Berkowitz: Speaking of Torah, what is learning like in Ein‑Makom? Shoteh: Naturally, traditional Jews learn more than the liberals, but both groups learn regularly, as far as I could tell. Tanya [a book of Jewish philosophy written by the founder of the Lubavitch movement] is a favorite; so is Maimonides. All of the children attend the same yeshivah. Berkowitz: Doesn't that pose a problem? Shoteh: Well, on most issues the traditional and liberal Jews agree. For example, you won't find a liberal Jew who drives his car on Shabbat or a traditional Jew who doesn't support the State of Israel. The few controversial issues are dealt with at home. Berkowitz: Besides Shabbat and support for the State of Israel, what are some other similarities between the two groups? Shoteh: There are many. One that impressed me was the concern for the environment. Jews in Ein‑Makom take car pools to work. They redeem their soda bottles at the local supermarket, and use very little plastic. In fact, on a Sunday morning, the two congregations get together and wash the dishes from the kiddush of the previous Shabbat. They don't buy paper plates or plastic cups, any of that stuff. Also, tza'ar ba'alei chaim [the prohibition against making an animal suffer] is quite important to them. So the people of Ein‑Makom don't buy products from the large soap and cosmetics industries because of the experiments performed on animals by those companies. Berkowitz: These people seem remarkably aware. Shoteh: They are. Especially when you consider how little of the various entertainment media they come in contact with. Most of the Jews in Ein‑Makom do not own television sets. They see very few movies ? because of the violence and lewdness ? and they dislike the New York Times. Berkowitz: They sound like chasidim! Shoteh: Yes, they are

like chasidim. For instance, they are very stringent

about giving tzedakah (charity). No one gives less

than ten percent of his income. But unlike some chasidim,

their money goes to a wide variety of institutions. The liberation of Jews in

captivity is important to them, so much of their tzedakah

goes to organizations working on behalf of the Jews in Berkowitz: You mentioned earlier that people give at least ten percent of their income. Isn't that a hardship? Shoteh: Not when you consider how little they spend on material things. A Mercedes or a Jaguar is unheard of there. No one would dream of wearing a thousand dollar suit or dress. By and large, the houses are spacious but unpretentious. People redecorate every twenty‑five years or so. Berkowitz: Excuse me for asking this next question, but from all that you have told me, the Jews of Ein‑Makom seem quite righteous but a little dull. Are they? Shoteh: It's odd that you mention that. A few years ago the traditional Jews noticed that they were growing smug and complacent. They decided to search for some new leadership, and hired a rabbi for their congregation. He is, in fact, the last of a long line of chasidic rebbes. Basically, he has revitalized the traditional Jews there. Berkowitz: How? Shoteh: Rav Elchonon makes it a point to visit the sick, comfort mourners, and dance at weddings. He checks mezuzahs, fixes the Torah scrolls, and gives classes in Chumash, Talmud, and Pirkei Avot. He's even performed a few conversions. He generally sleeps about three hours a night because he's always busy; sometimes he falls asleep during his own sermons on Shabbat morning. Berkowitz: I'm sure he's dedicated, but what makes Rav Elchonon so special? Shoteh: Imagine a short, wiry 50‑year old rabbi who will gather the young men of the town for a game of midnight basketball in the park, who arranges a boat trip on Long Island Sound to go whale spotting, and who keeps a telescope on his roof to chart the stars and planets. Also he plays the oboe horrendously. Berkowitz: I'd love to hear it. Shoteh: Well, of course you can't. As I said, the Jews of Ein‑Makom are wary of outsiders. Berkowitz: I have one last question. I am sure that Ein‑Makom is an exceptional community. But isn't it possible that you have overlooked some major flaw? It seems too good to be true. Shoteh: Of course it is. That is its major flaw. Ira Berkowitz lives and teaches in |

||||