|

||||

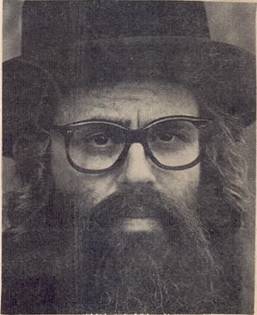

An Interview with the Slopeover Rebbe

Volume 1 , Issue 3

(March, 1988 | Adar, 5748)

Yisrael Lifschutz, filmmaker; hassidic actor, writer and artist has come to be known in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn as ?The Slopeover Rebbe?. In this exclusive interview with the Jewish Review editor Sandy Drob, Lifschutz speaks very candidly about his emergence into Jewish awareness and observance during the exciting and tumultuous years of the 1960's and 70's. In addition, he speaks about his award-winning film, The Return, and his role in, and behind the scenes impact on, the movie version of Chayim Potok's The Chosen. Jewish Review: What was it like for you growing up in Brooklyn and then in Belle Harbor, Queens? Lifschutz: My entire childhood was one

which was a very positive one. Iwas

very athletic and I remember playing ball night and day. I subsequently played

for my high school basketball team, played for the local little league and

played sandlot football. When we moved to Jewish Review: So you were out in the Rockaways as a teenager in the 1950's? Lifschutz: Right. I

went to Jewish Review: As a child were there any Jewish influences you can speak of? Lifschutz: I

grew up in a Jewish neighborhood and went to an

after school Hebrew School 2 or 3 afternoons a week and Sunday mornings. My

mother was particularly aware of her Yiddishkeit. Now

Yiddish was spoken by my parents but only as a means to keep me uninformed. I

remember sederim on Pesach at my maternal

grandfather's house. He was a unique character who is still very vividly etched

in my mind as a blacksmith who punched out his anti-semitic

sergeant in the Russian cavalry and went AWOL all the way to Jewish Review: They've both been gone for quite a number of years? Lifschutz: My

mother died when I was 17 and that probably triggered my whole Jewish story.

Down the block from me there was an Orthodox Jew who said to me "we have this

custom of saying Kaddish" and

I went for it because I was looking for some type of solace. I found it by

going to shul and saying Kaddish. There was a wonderful shammash in our synagogue who picked me

up every morning and took me to shul, and

by the end of the year I was able to daven from the Amud (lead the congregation). I wasn't shomer shabbat but I spent many a shabbat in the home

of the rabbi and various Orthodox families. But at the same time I was a senior

in High School and I was going to college and while I had this new attraction to Yiddishkeit,

I was becoming a young man who was attracted to the opposite sex and looking

for adventure and I wasn't about to become Orthodox then. I was looking ?for

many lives and many loves?, a person in search of what he was going to do for

the rest of his life. But Judaism certainly became a presence for me. After the

year of kaddish I still sometimes put on my tefillin, but for me kashrut at

the time meant that I would no longer eat a cheeseburger. I became enamored

with the concept of Eretz Yisrael and in 1961 I went to work on

a kibbutz in Jewish Review: Tell me what the 60's were like for you. I understand that you were friendly with a number of people who were in the music business at the time. Lifschutz: Right

here in Park Slope we had ?Steely Dan? and I used to hang outwith Becker and Fagan who at that time were the backup

band and arrangers for Jay and the Americans with whom I grew up in Jewish Review: When did you come to Park Slope? Lifschutz: Icame here in 1968. Jewish Review: What were you doing between 1960 when you graduated High School and 1968. Lifschutz: I

worked on newspapers. When the Six Day War broke out I went back to Jewish Review: So

back in the 60's you were not yet mixing Judaism with being part of the hippie

movement. Jewish Review: What brought you over into becoming a more serious religious Jew? Lifschutz: The particular story goes something like this. It happened during one of my many dropout periods. You have to realize I was also one of the people who "turned on, tuned in and dropped out." Iwould say that there was period that went on for about six years when I never had a job. I would do odd jobs here and there and I fortunately had a lot of good friends, etc. etc. But therecame this particular time when I decided "I gotta get a gig" and I went over to see my father, alav ha'shalom, who was a lawyer and I happened to run into a man in his office that day, a rabbi who was going to publish books on Kabbalah, Rabbi Phillip Berg. 'Rabbi Phillip Berg, the author of many books on Kabbalah including Kabbalah for the Layman and The Kabbalah Connection, (New York: Research Centre for Kabbalah) was a student of his uncle, Rabbi Yehuda Zevi Brandwein (1903-1969), a great Kabbalistic scholar who published editions of the works of Corduero, Luria and Vital and who wrote an important commentary on Tikunei HaZohar. Rabbi Brandwein was in turn a student of Rabbi Yehuda Ashlag (1886-1955) whose work is spoken of below. He asked me if I had ever heard of Kabbalah and I said "I think so" but I really didn't know what it was. He said "Listen, what do you do"? I said "I'm an editor, a writer." He said "I'm looking for someone just like you. Do you know Hebrew?" I said "Yeah." He said "Great, here's the manuscript." It was a 600 page manuscript and he says "I'll give you $1.50 per page to edit it." So I reckoned how much I'd make and I still don't have to go to an office! So I get on this train and I start reading something which is totally incomprehensible to me. First of all, structurally it was all one sentence. It was a Perush, a commentary on the ?Zohar, called ?Hasulam (The Ladder) by Rabbi Ashlag, about each of the letters going up to Hashem asking God to be the first letter of the Torah. I'm reading the manuscript which is totally incomprehensible, but I became so absorbed in it that I missed my train stop. So I got on the other side of the train platform. I read it again and I missed my stop again. I thought to myself that this could be like that song from the 50's, Charley on the MTA, about a guy who got on a subway train and never got off! So I closed it up and decided to read it when I got home. The editing went so slow, the concepts were so foreign that it was taking me five hours to edit a page and I realized that at the end of one week I had edited five pages and only made seven dollars and fifty cents! This was already late in the 60's and I'm not going to live on $7.50 a week. I realized "I can't do this," but I felt that it would be an embarrassment to my father, because Rabbi Berg was his client and my father had introduced us. I really felt I can't back out either. So I went to Rabbi Berg with my dilemma, and he said "Don't give up yet. When you do it, try wearing a yarmulke." I said "What! What are you kidding?" It was a very ludicrous suggestion but somehow I bought it.And the whole thing was Ihad a breakthrough in the work. Instead of one page a day I'm doing three. But three times $7.50 is still not enough. Meanwhile, editorial meetings with Rabbi Berg were also moving me in a new direction because I was taking time out to ask "What's the kabbalistic explanation for such and such." Rabbi Berg started to supply me with some answers that were making a lot of sense. Just to give you a brief example: I was an insomniac, and I said "I need to get sleep." He said to me "If you understand what sleep is all about it might be easier for you." "When you get to sleep," he told me, "your neshama (your soul) goes up to hashamayim (the heavens) and it gets replenished up there." Now, somehow with that concept in mind I started to learn how to go to sleep. I said "Wow," I'm doing this for the soul. I guess it was still on a selfish level, but I figured if its my soul that's going up, it somehow worked for me. And ultimately he helped me with all kinds of things like stopping smoking cigarettes, refraining from drugs, etc. etc. Jewish Review: Was he sort of your rebbe at that point? Lifschutz: Yes,

because who else did I know in the Jewish world? Months passed and I moved further along in my Yiddishkeit.

Rabbi Berg bought me tefillin when I was ready for

it. I started to feel that it was Shabbat on Saturday but I wasn't ready,

myself, to start going to shul. So

Rabbi Berg said "Since you're not ready for shul,

Shabbat is a day of rest, so sleep as much as possible, rest!" So that's one of

the things I started to do. After the yarmulke I still wasn't making enough

progress at my editing of Rabbi Berg's manuscript. He said to me: 'Why don't

you try going to the mikvah?? I had no idea what he was

talking about. I said ?What's the mikvah? Isn't that for women?? He took

me to the mikvah in Jewish Review: Was there a particular philosophy that Rabbi Berg had which attracted you? Lifschutz: As I look back on it now the philosophy was somehow that kabbalah, mysticism, was as American as apple pie. If you look at things like The Twilight Zone, if you remember these episodes which we all grew up on, many of them were kabbalistic or had kabbalistic concepts: ranging from reincarnation to astral projection. He pointed out that whatever people were into, say numerology, had a kabbalistic source or equivalent, in this case, Gematria. He was certainly able to relate it to a person of the 60's. Jewish Review: So you went about things in a way, which is the opposite of how it is prescribed traditionally? Lifschutz: Yes, but that was Rabbi Berg's particular school of thought as it was first pronounced by Rabbi Ashlag. While the traditional formula is to start with the observance, with Rabbi Berg you were first introduced to a certain kind of mysticism that was much more palatable than "Here, eat kosher! Put on tefillin!" Finally I made it to my first Shabbat at Rabbi Berg's and that first Shabbat was for me like LSD. Whatever I had taken on LSD and on all of these incredible mind-bending drugs I experienced on my first Shabbat. I'll give you an explanation of this. For many people that first Shabbat is so powerful. It's God's way of showing you potentially what there is. I haven't equaled that Shabbat yet. But I learned that what we know in the sixties with drugs could be attained naturally through Yiddishkeit. This was incredible to me. "Hey man, you want to get high, the way to do it is through Judaism!" Give me a break. Never did Rabbi Berg show any coercive tactics. After a time Ifinished editing the book, but mysteriously Rabbi Berg lost the manuscript and I had to do it all over again - I had a gig again! Jewish Review: Where did you go from there? Lifschutz: I

married Barbara. We had actually met in

Park Slope a couple of years earlier. We would run into each other every so

often and I had told her that I was editing a book on kabbalah

and it turned out that one day in June, 1971, she had been in a bookstore and a

book on kabbalah literally jumped off a shelf and hit

her in the head and she felt that that was a message for her to go talk to me.

She came to my apartment. I didn't happen to be home but we happened to meet on

Jewish Review: Did you learn at Hadar HaTorah? Lifschutz: I

would go Friday nights and Saturday mornings for shiurim and every so often during the

week, but now that I was married and had a kid right away I had to get serious

about making some money. I really didn't have the luxury of going to Yeshiva. I was reading as much as I could in

English seforim. Slowly I gravitated to a shul across the Park which was called The Prospect Park

Jewish Center, under Rabbi Abraham Kellman. I didn't

know what led me there but I think it was, in part, the walks through the park on Shabbat. Especially with my little 3 year old son, Isaac,

It was like being the Baal Shem Tov. There's lakes,

hills, horses coming by. Ever since I was a kid I remembered this Danny Kaye

movie where he walks over a footbridge and it's filmed in Jewish Review: What

made you stay in Park Slope all those years when there really wasn't an

Orthodox community here? Jewish Review: Do you still feel similarly? Lifschutz: Well, at this point, now that Park Slope is happening Jewishly, it's a very exciting time in our lives. Having been without a Jewish community all of these years and now that we're part of it it's very exciting. It's almost an answer to our prayers. And to have it here in Park Slope, because we have the only piece of country here in Brooklyn. Ihave a sled and yesterday I took the kids sledding. I don't want to overemphasize it but it's important. Also, we had friends here in Park Slope. The fact that I became religious didn't mean we had to leave our friends. There is also a teaching that a person should be happy where? he lives and I think, perhaps without making too much of this, that I was put here for some reason. We've always had people here for Shabbat, just to acquaint people with Yiddishkeit. Jewish Review: So you feel you had something of a role to play in Park Slope? Lifschutz: Once you become involved in Yiddishkeit you realize how important it is to have others who are growing in their Judaism with you. The real truth of Yiddishkeit, and that which will bring Messiah, is Achdut, unity. When Jews come together under one Torah, one set of laws, then the Messiah will come. You know to me, being a communications person, Torah means communication. When I'm talking Torah to somebody I feel that I am communicating on the highest possible level that I am able to communicate. Beyond film, print, radio, T.V. - talking Torah to people is the highest because through it you are connecting to Hashem. Jewish Review: Could you tell me how you got

involved in the movie The Lifschutz: For

one thing the producers of the movie had gone to Jewish Review: What were you hired as? Lifschutz: The

technical consultant. And the minute the director saw me he hired me for a part

in the movie. As technical consultant I

worked with the costume designers, the director, the production

designers, the make up people. I took all of it's stars around. I arranged for them to spend Shabbat

with different people. I took them to the four corners of Jewish life in Jewish Review: One thing I've always been curious about in The Chosen, something I had never heard about before and haven't heard about since is the way the father had somehow decided that silence was the appropriate way of relating to his son. Lifschutz: Yes,

at that time I found that it bothered me a great deal also. I felt that Potak had some kind of an ax to grind, that he was venting

certain anti-Hassidic feelings. It just

didn't make sense because for Jews our whole life is our children.

As a matter of fact, I got into a little trouble because during the course of

the shooting of the film I was involved with many of the public relations

people. I did interviews with the press where I had to give many a non- Jewish

reporter some background on Hassidus. One

time I happened to say to a reporter from the Jewish Review: You also played the coach of the baseball team. Lifschutz: I

had 3 lines, only 2 of which were involved in the final version of the film.

Since then I've been in a number of other movies. Most recently I did a film

with Michael J. Fox called Jewish Review: In all of these you played a Hassid? Iguess that's where you get the reputation of being the world's leading Hassidic actor. Lifschutz: You

have to realize that I founded

the Hassidic Actors Guild or HAG. Our motto is "pay us for pais."

But wherever there is a Hassidic hook or element in a film (except for extra

parts) I've been involved. Also I was a technical consultant and appeared in

several segments of Civilization

and the Jews. I did a scene with Abba Eban in

Bedford Stuyvesant in the shul on Jewish Review: What kind of business are you in now? Lifschutz: In

public relations and advertising. We also make corporate and organizational

films. Last year I was in Jewish Review: Could you tell us something about your current film projects? Lifschutz: Yes,

I amabout to spend two

weeks in Israel where I'll be shooting a piece with ABC radio's prime time talk

show host Bob Grant. Grant, who is not Jewish, is a long time supporter of Jewish

Review: Where will people be able to see this film when it is

finished? Jewish Review: How did you become known as the ?Slopover Rebbe?? Lifschutz: Well, I've alsocalled myself the "hipover rebbe": you see Iwasn't always religious, so I used to be "hip". I've had a couple of different hassidic rebbe monikers but "Slopover" just seemed to work. Jewish Review: A dynasty? Lifschutz: It should be so. However, when Rabbi Shimon Hecht moved into Park Slope I was glad to relinquish my title to him, but in his humility he said ?I would like to be the Slopover Rabbi and you can remain the Slopover Rebbe.? It's a great line; as a smart aleck response it works. Jewish Review: You're also an artist. Could you tell us something about your artwork? Lifschutz: Well,when the Six Day War broke out and I left the Daily News I tried to write a novel, and I also tried to develop my artistic side. I got very heavily involved in pen and ink and I've had my work appear in a number of magazines. When I got into Yiddishkeit I was able to name each of my works with pissukim, biblical verses. They're abstract pen and inks based on pissukim. They arevery time consuming. I'd like to get involved in doing them again but some of them took me 2 months working 9 to 5. When I think ofJewish art or Jewish film I think of it as a means of conveying, to both Jews and non- Jews, a celebration of Judaism. I always wanted to be into films and then when I got into Yiddishkeit I gotinto films. Jewish Review: Then Yiddishkeit was your ticket to getting involved in films? Lifschutz: Well, somehow I got an answer. Judaism seemed to open doors. It was like another divine goof: ?"You want to be in movies? Become Jewish." Jewish Review: For many baalei teshuvah a major issue involves integrating Judaism with the rest of their lives, the lives they had before they became religious. How do you feel you've succeeded in doing that? Lifschutz: Certainly becoming religious,

bearded, Orthodox has opened doors for me, enabled me to find a little niche

for myself in Jewish Review: In some ways you're a paradox. Because the previous generation felt that in order to realize their American dreams they had to cut off their beard and look more American and you did just the opposite. You became more American or more successful as an American by becoming more Jewish. Lifschutz: I guess you could see it that way. One thing you need to have as a Jew is the emunah, the faith that whatever you do God will still be with you. I wear the beard and kipah and I would never think of taking either one of them off, and they certainly haven't limited me in any way Jewish Review: Is there room in the world for too many people like yourself or are you in some ways unique? Lifschutz: No, I'mjust one of many, many examples. The Baal Teshuvah movement which I've been documenting on film and video for the past 10 years is very rich. I've met many other people who have been given a bracha to use their talent for Yiddishkeit. Take television for example. Why not raise this medium to the level of Kedushah and give parents the opportunity to provide their children with an alternative to what's programmed there. Especially now that we have VHS equipment there is an opportunity for a big boom in Jewish video. So much of TV goes against the values of Judaism. But now there are video-tapes being marketed in Jewish book stores by a variety of people. There is certainly a place for creative people in Judaism. Take a look at the artist Michoel Muchnik who we featured in our documentary The Return and who you interviewed in your last issue for example. He said "I always knew how to paint but until I got into Yiddishkeit I didn't know what to paint!" I felt the same way with film. There's room for anyone in Judaism with or without a particular talent. |

||||